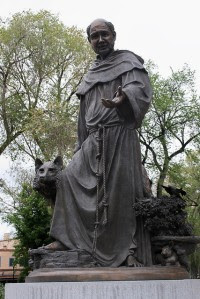

St. Clare of Assisi (1194-1253), best known as St. Francis’ “little plant,” eventually emerged as a strong leader in her own right in thirteenth-century Italy and beyond. While St. Francis took center stage with his extraverted charismatic leadership, St. Clare quietly built stronger structures behind the scenes.

As I muse on St. Clare and her contributions, three leadership lessons stand out for me. Clare teaches me about prayer, community-building, and persistence.

First, Clare knew the power of prayer. She knew that prayer provided the foundation for all of her leadership. Without prayer, without her radical trust in God, she could do nothing. She prayed for strength and guidance when she was called to lead her community of “Poor Ladies” as a young adult. Later, when an invading army swarmed her vulnerable convent of San Damiano, outside the protection of the city walls, she prayed. Upon praying, she felt led to stand at the window in front of the army, armed only with the host, the body of Christ, and her trust in God. Faced with Clare’s shining strength, the army became confused and fled. Thus, through prayer, Clare saved not only her convent but also the city of Assisi. Finally, Clare’s prayer undergirded her day-to-day leadership in the convent. When faced with lack of food, with illness, with cold, she prayed. People brought turnips, medicine, and blankets, and year after year, all the Sisters’ needs were supplied.

Second, Clare knew how to build community. Though she lived in an enclosed community at San Damiano her entire life as a Sister, she built community both at home and afar. She showed her 50 fellow Sisters how to live together in compassionate service in cramped quarters and difficult conditions. Beyond San Damiano, she instructed Agnes of Prague, a princess who left behind wealth and status to found a religious community like Clare’s, in building a convent. While Francis’ communities faced divisive conflicts, Clare taught her communities to work through conflicts in ways that built stronger relationships. And she also built relationships near and far, with St. Francis and his brothers, with priests, with bishops, and with Popes.

Third, Clare lived perseverance. Her entire life, she fought for a way of life like Francis’ in which she could be true to the gospel as she understood it. For her, this meant living in poverty, in total reliance upon God. She appealed to every Pope in her lifetime to approve the rule she had written to regulate life in her community. When Pope after Pope said no, she didn’t give up. Finally, on her deathbed, the Pope sent word that he had heard she was dying and he wondered if there was anything he could do for her. When she said, “Approve my rule,” he relented, and she received papal approval two days before she died.

Leading with soul is never easy, whether one lives in thirteenth-century Europe or modern times. The way is often fraught with stresses, discouragements, and obstacles that challenge our commitment to walk our path with faith. However, we can turn to those who have come before us, those like St. Clare who embody the qualities of a good leader. They show us not only that it is possible to lead with soul but also that we are not alone in the journey.

(This article first appeared in April 2016.)